Texture Atlas Maker

**2012 UPDATE**: I have released a new version of AtlasMaker with many more features. Check it out here!

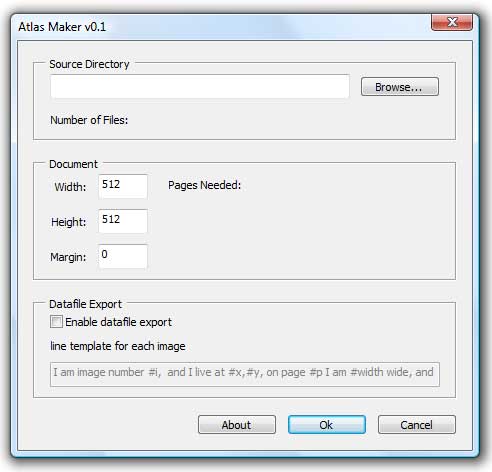

As I promised last time, here is a photoshop script for creating texture atlases from a directory of images. The script uses a rectangle packer class written by Iván Montes which is itself based on an article by Jim Scott. All I really did was add a GUI.

Instructions

AtlasMaker works in much the same way as the SpriteGrabber script I wrote a few weeks ago. Unzip the AtlasMaker directory somewhere, then in Photoshop, go to File->Scripts->Browse and load AtlasMaker.jsx. The script should then run automatically.

To create a texture atlas, click browse and select the directory containing your textures. The script will then process each image to get the information it needs to make the atlas. Once this is done, you can modify your destination document size, or add an optional margin around each image. AtlasMaker will create as many pages as it needs to hold all the images.

To create a texture atlas, click browse and select the directory containing your textures. The script will then process each image to get the information it needs to make the atlas. Once this is done, you can modify your destination document size, or add an optional margin around each image. AtlasMaker will create as many pages as it needs to hold all the images.

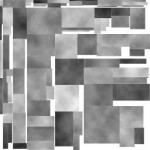

When you are ready, click ok and AtlasMaker will generate the texture atlas, with each texture on its own layer. You should end up with something like the image on the left.

Datafile Export

If you tick the “Enable datafile export” checkbox, AtlasMaker will create a text file in the src directory called “AtlasInfo.txt”, containing a line of text for each sprite.

Each line is generated from the text entered into the “line template” edit box. Tags are used to substitute information about each sprite into the text.

#i – Image index (0.. number of Images in directory)

#filename – Filename of source image

#width – Sprite width

#height – Sprite height

#x – X position of top left corner on spritesheet

#y – Y position of top left corner on spritesheet

#p – page number

Lets say your game engine loads textures or sprites like this: “TextureManager->GetTex(x,y,width,height);” and you have 50 images to load. You can generate all 50 calls by entering the following into the line template box:

TextureManager->GetTex(#x,#y,#width,#height);

SpriteGrabber will then generate 50 lines containing the correct coordinates and dimensions for each Image.